Welcome to the first issue of my relaunched newsletter. If you subscribe I’ll send you a free copy of my Microcosmos Fiction Magazine, containing five original stories. Thanks for reading.

Notes on places

A milestone in Nutley

Strung along the A22 like grave markings for a vanished transport system, the Bow Bells milestones punctuate the old coaching route between Eastbourne and London. This example is from the village of Nutley in the Ashdown Forest. The milestones were installed by the turnpike trust that managed the road during the eighteenth century. Given that the Ashdown Forest was a centre for the iron industry, it’s likely the signs were made locally. The straightforward approach would have been to inscribe them with the destination ‘London’, but someone, a proto-brand manager in the trust or a bright spark in the ironworks, had the idea for something more creative.

The bells of St Mary-le-Bow on Cheapside, the Bow Bells, whose sonic embrace forms the cradle of all true Londoners, are used as a metonym for London. And the metonym is represented by a rebus, three bells topped by a bow. It’s a sophisticated piece of imagery. The old coaching routes had their own systems of measurement and time-tabling, too. Standard time across Britain only came with the spread of the railway network. Though the standard, ‘statute’ mile was introduced by an Act of Parliament in 1593, local ‘mile’ measurements remained in use well past this date. Each of these antique milestones is a reminder of a space-time less uniform.

Notes on reading

Wernher and Walt

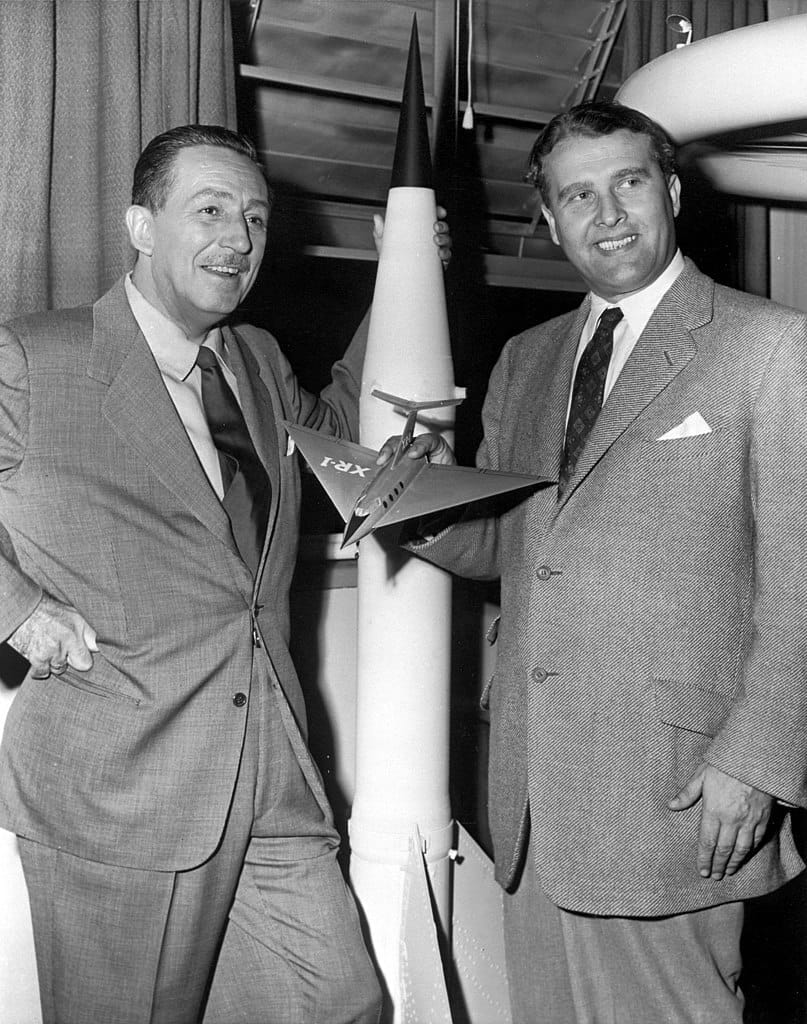

Anyone interested in the history of space exploration will be familiar with the name of Wernher Von Braun and the main points of his biography. They’ll know that Von Braun was a German aristocrat, SS officer, and scientist. They’ll know he led the Nazi’s rocket development programme, designing the V-2 rockets which terrorized London towards the end of World War Two. And they’ll know that Von Braun and his team were spirited away to the United States at the end of the war, absolved of any wrong-doing, and established in a Texas research facility. Von Braun went on to make an critical contribution to the American space programme, including the design of the Saturn V rockets that propelled the Apollo moon landings.

What the amateur space historian might not know, and I certainly didn’t until I read John Higgs’ book, Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century, is that in the mid-1950s, Von Braun made three films on space exploration for Disney Studios, for the television series, Walt Disney's Disneyland. According to Higgs, this was ‘an effort to increase public support for space research’ (which was to remain in the doldrums until the Soviet Union launched its Sputnik 1 satellite)

The first two episodes, ‘Man in Space’ and ‘Man and the Moon’, were aired in 1955. The third, ‘Mars and Beyond’, appeared in 1957. Walt Disney himself introduced ‘Man and Space’, and spoke of combining ‘the tools of our trade with the knowledge of the scientists to give a factual picture of the latest plans for man's newest adventure’. ‘Man in Space’ can be viewed on YouTube, with von Braun appearing every inch the suave, aristocratic scientist.

Von Braun had been interested in rocket science and space travel since childhood. Although entitled to call himself a Freiherr, or Baron, he was no aristocratic dilettante. By the time World War Two broke out he knew more about rocket science than any man on Earth. He was also a member of the Nazi party and an SS Sturmbannführer, the equivalent of a major. It was, of course the only way to get on in Germany at that time, and the only way for von Braun to pursue his research. Still, when he became chief scientist at the Mittelwerk factory he must have known what he was getting into. This underground plant was where the V-2 rockets were produced. It had been excavated by slave labour and slave labour worked its production lines. Higgs describes it thus:

Over twenty thousand slaves died constructing the factory and the V-2. Mass slave hangings were common, and it was mandatory for all the workforce to witness them. Typically twelve workers would be arbitrarily selected and hung by their necks from a crane, their bodies left dangling for days. Starvation of slave workers was deliberate, and in the absence of drinking water they were expected to drink from puddles…Von Braun himself was personally involved in acquiring slave labour from concentration camps such as Buchenwald.

Why wasn’t Von Braun tried and executed for war crimes after the collapse of Third Reich? Because the Americans wanted to use his expertise to develop their own rocket programme. Records of his war-time activities were destroyed or suppressed, and Von Braun was shipped off to a new life in the United States. And then Walt Disney came calling. I can’t imagine that Walt knew much about Wernher’s past, but even if he did, the main enemy now was the Soviet Union. The story goes that when the young von Braun met the Swiss physicist, Auguste Piccard, in 1930, he told him, ‘You know, I plan on travelling to the Moon at some time’. Though he didn’t make it there himself, he lived long enough to see twelve American astronauts get there in a rocket of his design.

Von Braun died an honoured and respected US citizen in June 1977. He never had a Disneyland ride named after him, but he did get a biopic, albeit not from Disney Studios. In the film I Aim at the Stars, he was played by Curt Jurgens. I’ve never seen the film but even when it was released back in 1960, it was viewed by many as a whitewash. Von Braun’s is an astonishing life story, and in its way, a very American one. In the space of ten years, he had gone from being a senior SS officer to a children’s television presenter. By the time another ten years had elapsed, he had an office at NASA and a senior position in the Apollo programme. That’s quite a story arc.

Notes on writing

Portraits in words

A couple of novels I read recently got me thinking about character descriptions in fiction. Here’s one from Rosamond Lehmann’s 1927 novel, Dusty Answer:

Roddy scarcely ever spoke. He had a pale, flat face and yellow-brown eyes with a twinkling light remote at the back of them. He had a ruffled dark shining head and a queer smile that you watched for because it was not like anyone else’s. His lip lifted suddenly off his white teeth and then turned down at the corner in a bitter-sweet way. When you saw it you said ‘Ah!’ to yourself, with a little pang, and stared, — it was so queer. He had a trick of spreading out his hands and looking at them —, brown broad hands with long crooked fingers that were magical when they held a pencil and could draw anything. He had another trick of rubbing his eyes with his fist like a baby, and that made you say ‘Ah!’ too, with a melting, quick sort of pang, wanting to touch him. His eyes fluttered in a strong light: they were weak and set so far apart that, with their upward sweep, they seemed to go round the corners and, seen in profile, set in his head like a funny bird’s. He reminded you of something fabulous — a Chinese fairy story. He was thin and odd and graceful; and there was a suggestion about him of secret animals that go about by night.

Now that kind of writing isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but I think it’s wonderful. What reader wouldn’t feel they knew quite a bit about Roddy after reading that? This next example is from John D MacDonald’s in his 1965 book The Deep Blue Goodbye, the first to feature his best-known protagonist, Travis McGee:

She was a tall and slender woman, possibly in her early thirties. Her skin had the extraordinary fineness of grain, and the translucence you see in small children and fashion models. In her fine long hands, delicacy of wrists, floating texture of dark hair, and in the mobility of the long narrow sensitive structuring of her face there was the look of something almost too well made, too highly bred, too finely drawn for all the natural crudities of human existence. Her eyes were large and very dark and tilted and set widely. She wore dark Bermuda shorts and sandals and a crisp blue and white blouse, no jewellery of any kind, a sparing touch of lipstick.

This is masterful. While MacDonald’s eye is cooler than Lehmann’s, he’s no less attentive to the details of the character. Perhaps the main superficial contrast between the two is that Lehmann is writing literary fiction, whereas MacDonald sits firmly in the crime genre. But whatever the genre, extended character descriptions like these are rarely seen in present-day fiction. Brevity of description, verging on stinginess, is the current mode.

I expect most writers would say that readers these days don’t have the patience for it. They may be right. But I wonder if many writers don’t have the patience for it either, by which I mean the patience to really imagine a character and what they are like. Those of us who write genre fiction know the importance of driving the story forward, of not wasting words, of not dwelling on details that aren’t significant to the story. There is also, I think, a view that ‘something should be left to the reader’s imagination’, that, to use engineering language, the solution should not be over-specified. Modern literary theory is adamant in its view that the reader is the co-creator of the text.

I wonder too if our predominantly visual culture may have something to do with it. We all have minds full of images, still and moving, far more than I’d guess Lehmann did and probably more than MacDonald did too. It’s easy enough for a writer to provide a few visual prompts for a reader to pick up and merge into a character from film or television who already inhabits their thoughts. I’ve heard some writers say that they cast their characters, that they imagine which actor would play the part if the book was turned into a movie. Perhaps, consciously or not, once they’ve cast the role, the writer is less inclined to describe them fully.

These reflections have made me realize how much I need to improve my own character descriptions. I doubt I’ll ever go the whole Lehmann, so to speak, but even in genre fiction there is room for more detail and more nuance than I’m currently achieving, as MacDonald so stylishly demonstrates. Note to self: be patient and really imagine the people you’re writing about.

From the photo album

Fallen angel, Aylesbury