Welcome to the latest issue of my newsletter. If you subscribe I’ll send you a free copy of my Microcosmos Fiction Magazine, containing five original stories. Thanks for reading.

Notes on places

An anchoress in Shere

How good a thing it is to be alone, is manifested and shewn both in the Old Testament and also in the New. For in both we find that God revealed his secret counsels and his heavenly mysteries to his dear friends, not in the presence of a multitude, but when they were by themselves alone.

Early in the summer of 1329, Christine Carpenter, a young woman living in the village of Shere in Surrey, petitioned the Bishop of Winchester, seeking permission to become an anchoress. Several men of the village, including Christine’s father, William (a carpenter by trade), were asked to vouch for her devoutness and virginity. The answers must have been satisfactory because in July of that year Christine was, with due ceremony, locked in her cell in the north wall of St James’ Church, also in Shere, and so began her new life of solitude and contemplation.

The remains of the cell are still visible. The photograph above shows the exterior (centre of frame). There would have been some kind of opening through which Christine could communicate, receive food and have her bodily waste removed. My guess is that the cell was about five feet high, three feet wide, and a foot and a half deep.

At some point in the next three years, Christine decided that the life of an anchoress was not for her. She left the cell, though by what means and with whose help is unknown. In her article for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Liz Herbert McAvoy writes that after her release, Christine ‘was seen to be “gadding about” the countryside, engaging with the dangers of sinful temptation, and in her wanderings presenting a ready prey for the devil’.

Then Christine had a change of heart, perhaps because she was facing excommunication for having reneged on her sacred vows, perhaps because she wished to recommence the holy life, perhaps a bit of both. In the autumn of 1332, she asked the Bishop to allow her to return to her cell. Permission was granted, but this time her enclosure was to be permanent.

The Episcopal Register of the time contains a communication to the Dean of Guildford, in which the Bishop orders that ‘the said Christine shall be thrust back into the said re-enclosure, and that with suitable solicitude and competent vigilance you shall take care to guard her, thus enclosed, in due form, that she may learn at your discretion how nefarious was her committed sin, and that thereafter dedicating herself worthily to God, having first offered to God that which is inflicted on her by us, she may be enabled to achieve her salvation’ (quotation from the St James’ Church pamphlet, ‘Christine Carpenter, The Anchoress of Shere’). Professor McAvoy says it is likely that the wooden door of the cell was removed and Christine was then walled in.

The photograph above shows, on the left, the quatrefoil opening (squint) through which Christine would have received communion. On the right is the squint through which she could see the altar. When and how Christine Carpenter died is unknown, but it’s unlikely that she ever left the cell again.

Notes on writing

Tools of the trade

Without Qwert Yuiop’s willingness to submit to my punishing fingers I doubt if I could have sustained the profession of author. I know how to use a pen, but ever since I took my last written examination, the pen has always been for me a musical instrument: I still write orchestral scores with it but, associating it as I do with the shaping of notes and dynamic signals, I find it difficult to put it in the service of any written statement longer than allegro ma non troppo…

Qwert Yuiop in his traditional form…not only relates authorship to artisanship; he separates the written from the writer (a pen is too close to the heart) and brings him closer to that objectification which only the final printed copy can bestow. A writer does not pour out his heart or even talk on paper. He creates an artifact.

In the extract above, Anthony Burgess is talking about his trusty manual typewriter when he talks about ‘Qwert Yuiop’. He was writing in 1986, before the advent of the mass-produced, general-purpose personal computer, but a time when special-purpose word processors were edging out the typewriter. Burgess himself, as he says in the same essay, had just ordered his first such machine: ‘As I write, an IBM word processor with daisywheel sits malevolently waiting for me in a customs shed’. Burgess had skipped a generation of technology by refusing to engage with electric typewriters. He had another seven years of life left and published four novels in that time, though, as far as I know, he never recorded his experiences with the malevolent IBM device.

Every writer has their tools of the trade, and for most of us now it’s a computer. The manual typewriter may have gone the way of the quill pen, but there are still some who prefer to write longhand, especially for the first draft. Colm Tóibín was on BBC Radio 4’s Poetry Please programme a while back. He has a considerable reputation as a novelist but has also published verse. I was intrigued when he said that his novels are all written longhand, but he types his verse on a computer. This surprised me because it seemed to reverse the usual order of things.

Yet why should I think that? I suppose because I have an unexamined assumption that writing verse is more emotional, more intimate, less objective, than writing a novel or short story. Poems, it seems to me, come from the heart in a way that novels don’t. Of course, I’m generalizing — there are always exceptions. But a computer is surely designed for the heavy construction of novel-writing, not the delicate contriving of verse.

I’d guess that almost all commercial fiction writers, and most literary ones, apart from those of a certain age, take the Burgess approach rather than the Tóibín one to novel writing — ‘a pen is too close to the heart’. Poets, on the other hand, should surely favour the pen. So I’d guess Tóibín is the exception in both spheres.

I’m old enough to remember when there was a certain sniffiness about word processing and fiction writing. I remember too once reading AS Byatt say that she could always tell when a book had been written on a computer. She didn’t intend it as a compliment. But people once said the same about typewriters. For many traditionalists, the computer is an alienating technology, an inhuman intermediary between the mind and the page. It’s never felt like that to me. I couldn’t give up my laptop and I’d find it very difficult to produce a book with pen and paper. Still, people managed it once upon a time.

Leaving aside the pen, it astonishes me now that the old pulp writers (and indeed prolific writers of literary fiction like Burgess) hammered out their words and works on manual typewriters, unable easily to correct or amend or insert. What an incentive for a clean and coherent first draft that must have been. The tools make the writer, I suppose. The word processing program is an invitation to endless, and eventually self-defeating, rewriting and reworking. I think, more and more, that it encourages sloppiness of thought and expression. It’s so easy to type mediocre or even bad prose and tell yourself, ‘I’ll sort it out on the next draft’. Yes, I’m talking about myself there.

Photograph of Antony Burgess at his typewriter © International Anthony Burgess Foundation.

Notes on reading

The cutting room floor and after

We went down downstairs to the little dark-green room with lamps hidden behind green silk and sat down and listened to the band playing blues and watched the hips and breasts of the women dancing and drank and smoked those sweet American cigarettes which taste as if they are drugged.

In Bloody Murder, his history of crime fiction, Julian Symons called it ‘the detective story to end detective stories… a dazzling and perhaps fortunately unrepeatable box of tricks’. More recently Jeff Noon, in a Spectator review, described it as ‘a bit like Somerset Maugham meeting James Joyce in a dark alleyway in Soho and one of them ending up dead, and the reader not quite able to work out which one’s the victim, and which the murderer’.

I’d read a few references to Cameron McCabe’s novel, The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, over the years and had half-remembered it as a possibly interesting novel I might get round to reading someday. Though the book was first published in 1937, Cameron McCabe, whoever he had been, was not a name that cropped in the standard discussions of detective fiction’s Golden Age. I guessed the book was a one-off, an oddity, whose author had vanished into obscurity.

Picador Classics reissued it a few years ago, with an introduction by the novelist Jonathan Coe, and that’s the edition I got round to reading at last. I have to tell you, Reader, I was disappointed. That said, the book gets off to a cracking start. 1930s London — its high and low streets, pubs and nightclubs, smart apartments and cheap lodgings, the film studio where most of the main characters work — is evoked in sparing but telling detail. Much of the speech is peppered with an Americanized slang, which may or may not be how hip Londoners spoke at that time. And not far into it, you realize that Cameron McCabe is not only the name of the author but also the name of the protagonist, the first-person narrator. What’s going on there?

I won’t describe the plot, but the inciting incident is the apparent murder of a young actress in one of the studio’s cutting rooms, an actress whom McCabe, a film editor, has been asked to excise from a film that’s just been shot. The investigation is led by an Inspector Smith of Scotland Yard, a most peculiar detective who gets more peculiar as the story progresses. Indeed, the whole novel gets more peculiar as it progresses, and not, I think, in a good way. McCabe the author plays with his readers, using devices such as the unreliable narrator, a kind of post-modern deconstruction, and what Coe identifies as Brecht’s alienation technique. It all gets very tedious after the opening third.

But I got to the end of it and then read the Afterword, the bulk of which is an interview with the author. It turns out that the real Cameron McCabe was a much more intriguing character than the fictional one. Ernest Borneman, a Jew and a member of the Communist Party, fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and was granted asylum in England. Four years later, when he was just twenty-two, he published The Face on the Cutting Room Floor.

He published two more novels (not as Cameron McCabe), worked for the BBC, collaborated with Orson Welles, set up West Germany’s public television service, and wrote extensively on the history and forms of jazz music. Then, in the mid-1960s, after a long interest in psychoanalysis, he embarked on a course of scientific research into sexuality, eventually becoming one of Germany’s leading sexologists. The interview in the Picador edition provides a lot more detail and incident than I can go into here, but as careers go, that’s quite a varied one.

Talking about his first novel, Borneman says, in a letter also included in the Picador afterword, that he wrote it when he was nineteen, a refugee newly arrived in London. The novel ‘was meant to be no more than a finger exercise on the keyboard of a new language. It had no message and wasn’t meant as a spoof on the great masters of the crime story. I simply wanted to know if my English was good enough to let me earn money with my pen’. Its cult status puzzled him. ’I shall never know why The Face on the Cutting Room Floor, which seems mannered and puerile to me now, has been re-issued so often…’

Borneman’s assessment of his first novel, written at a distance of forty years, is a little harsh, but he’s right about it being mannered. Still, it’s an extraordinary piece of work for a very young man still adapting to a language and a culture not his own. I’m glad I read it and I don’t regard that time as wasted. And now I know more about the man behind the pseudonym, I’m intrigued enough to want to read his two other novels, which he rated much higher than that first.

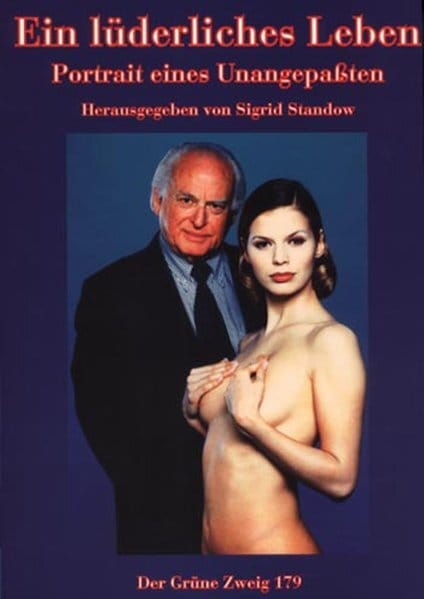

Borneman died in 1995 in Germany. His was a not a peaceful death. When a colleague half his age left him for a younger man, he took his own life. It was a plot twist worthy of a crime novel. Just two months before his suicide, the colleague concerned, Dr Sigrid Standow, had arranged the publication of a festschrift to celebrate Borneman’s 80th birthday. The cover of the book featured a photograph of Standow, naked, in front of a besuited Borneman. What a novel his own life would make.

From the photo album

Scenic ruin, Aylesbury