Welcome to the latest issue of my newsletter. If you subscribe I’ll send you a free copy of my Microcosmos Fiction Magazine, containing five original stories. Thanks for reading.

Notes on places

A visceral experience in Juniper Wood

He stroked their muzzles sometimes.

He was a kind man.

And he gave them no promises:

when the trap’s teeth snapped shut,

their own light feet had triggered the spring

We were walking through Juniper Wood when we saw these outgrowths gleaming on the ground like some rare and improbable fungi. ‘Gralloch,’ one of my companions said, and then, ‘Poachers’. Gralloch is a word derived from the Scottish Gaelic grealach, ‘entrails’. In its noun form, it refers to the viscera of a dead deer, and, as a verb, means to disembowel a deer that’s been killed. Gralloching must be done quickly after the kill to prevent to the meat from being spoiled or contaminated.

According to the Deer Initiative Partnership, deer are more abundant in Britain than at any time in the last thousand years. Native species are flourishing and non-natives like sika and muntjac are firmly established. Left unchecked, deer can cause significant damage to vulnerable habitats such as woodland. Regular culling of the deer populations is necessary. Deer poaching could be seen as a kind of freelance culling, though whatever outlaw romance it may once have possessed is long gone.

I’ve heard it said that you should only eat meat if you’re prepared to kill it yourself. That seems plain daft. Civilization is built on the division of labour. We have people to kill the beasts, and others to cut them up and prepare them. Just as we have people to design integrated circuits and others to build them. I don’t want to kill my own meat any more than I want to build my own integrated circuits. Which isn’t to say that there aren’t serious moral and environmental problems with the ways in which the food we eat gets onto our plates.

Stumbling across the remains of the kill provoked, forgive the pun, a visceral reaction. It felt intrusive, almost indecent, to stop and photograph. For a moment, there was a sense of peering in on some ancient hunter-gatherer rite. I’m as detached as any city dweller from the bloody mechanics of animal killing, whether on the small-scale of the poacher or the industrialised slaughter of the meat processors. It’s as well to be reminded that actual, living creatures die to sustain us, and to think about how and what we eat.

Flash fiction

After Easter Island

Fleeing a collapsing ecosystem and the predations of slave-raiders, the Easter Islanders set sail in search of new lands. After a century or more of sea-wandering, they made landfall at the Isle of Sheppey, where they survived by carving statues of their ancestors for sale at garden centres.

Notes on reading

Peter Jackson's strange London

One day at primary school, when I was searching the classroom cupboard for something — glue or tracing paper or perhaps even an escape route — I found a book of comic strips on one of the shelves. I opened it on a page with a panel titled THE UNSOLVED MYSTERY OF SCOTLAND YARD. The accompanying illustration showed a bearded head with dead white eyes and the kind of face that appears in nightmares. The rest of the text read: IN THE ‘BLACK MUSEUM’ IS A PLASTER CAST OF A MURDERER’S FACE — WHICH HAS GROWN WHISKERS! ALL THE EXPERTS OF SCOTLAND YARD HAVE FAILED TO SOLVE THE MYSTERY. I had never heard of this Black Museum. Was it, like the British Museum or the Natural History Museum, a place accessible to eight-year-old boys?

I’d been granted a glimpse into a previously hidden world, a world in which strange phenomena were real, attested, and documented in comic strips. I was hooked. I asked my teacher, whose book it was, if I could borrow it. That evening I read it from cover to cover and back again. Several obsessions sprang from that encounter.

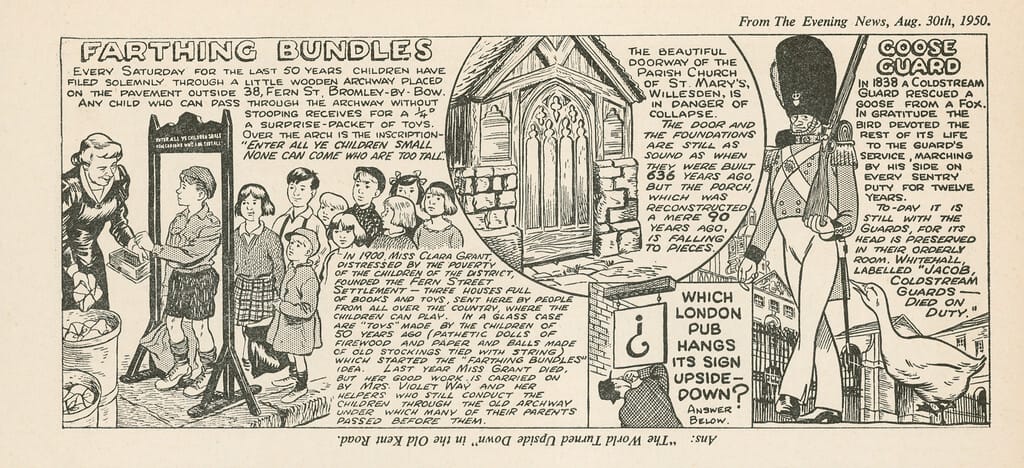

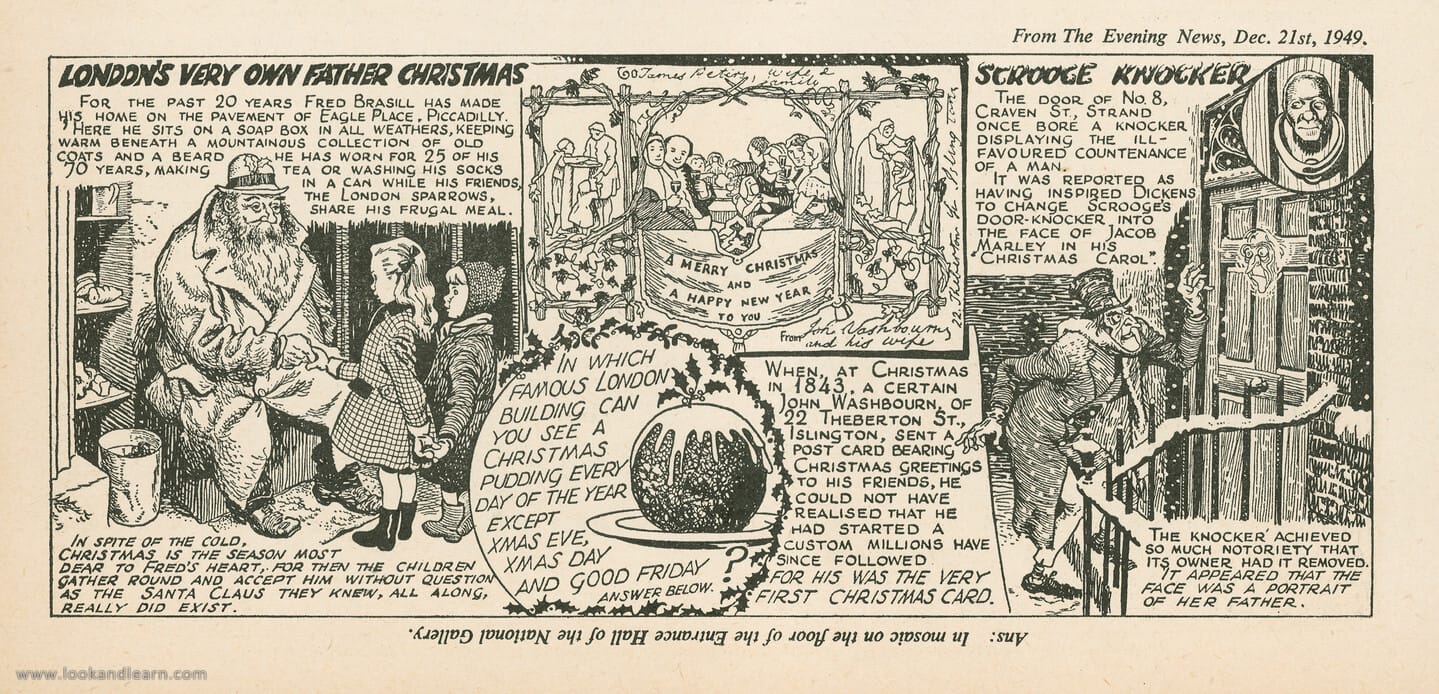

The book was a set of reprints of Peter Jackson’s comic strip London is Stranger Than Fiction, which appeared in the Evening News from 1949 to 1951. Jackson was only twenty-six when he got the job after submitting a few drawing to the newspaper’s editor, who wanted to introduce a strip similar to Ripley’s Believe It or Not. He produced two other London-themed series for the paper, London Explorer and Somewhere to Go.

Though the London is Stranger Than Fiction strips are primarily concerned with history, with past people, events and places, they also include a rich cast of then-living Londoners: Mrs Molly Moore of Camdenhurst Street who has been ‘knocking up’ her neighbours with a peashooter for over 30 years; Mrs Violet Way of Bromley-by-Bow, who distributes farthing packets of toys to local children passing under a wooden arch inscribed ‘Enter all ye children small. None can come who are too tall’; ‘Bulky landlord Len Cole’, proprietor of the smallest pub in London, the Nag’s Head in Kinnerton Street; Conductor Sweeney of the 53 bus route, who was once of Master of the Household to a Russian princess; Mr John Fain of Love Lane, who makes the flat-topped leather hats that Billingsgate porters wear to carry boxes of fish on their heads; and Fred Brasil, ‘London’s very own Father Christmas’, who lives on the pavement of Eagle Place.

The contemporary London portrayed in Jackson’s series has barely recovered from the war. References to buildings erased during the Blitz are common. The pall of loss and austerity hangs over the city. Around 20,000 Londoners have died in the Blitz, food and petrol rationing won’t end until the Fifties, and reconstruction has yet to begin. Yet there is humour and optimism. London and most of its people have survived: London has taken it.

More than half a century on, development and demographics have changed London as irrevocably as the Great Fire and the Blitz did. Jackson’s eccentrics and practitioners of odd trades are gone, as are most of the quirky customs and curiosities he describes. It’s an irony of history that despite the freedoms and opportunities of our current age, the London of today appears deeply conformist in comparison with the city portrayed by Jackson. Much of the London of the mid-century imagination has vanished or is barely recognisable. And I still haven’t been to the Black Museum.

PS All the London is Stranger Than Fiction and London Explorer strips have been collected and published a single volume by the Look and Learn Historical Picture Archive. Individual strips can also be purchased from the Look and Learn website.

All images by Peter Jackson © Look and Learn

From the photo album

Man vs Nature, Aylesbury