Welcome to the latest issue of my newsletter. If you subscribe I’ll send you a free copy of my Microcosmos Fiction Magazine, containing five original stories. Thanks for reading.

Notes on places

A toad encounter

We are far too busy

to be starkly simple in passion.

We will never dream the intense

wet spring lust of the toads.

There are only two native toad species in Britain and one of these, the Natterjack Toad, is rare, confined mainly to a few coastal sites. So the chances are that if you come across one in the wild, it will be a Common Toad. I met the one in the photograph on a bank of the River Wey, between Guildford and Woking. She — I think it was a female — was sitting right on the towpath used by cyclists and walkers, and stood a fair chance of getting squashed. I picked her up — how thin her skin felt, how fragile her tiny bones — and put her closer to the river, out of harm’s way. She waited a moment or two and then heaved herself under the grass. There was something impressive about her imperturbability and lack of hurry, and I got a strong sense of how solid and fearless these creatures are. It’s no surprise that toads can live for up to forty years.

Folk biology distinguishes between frogs and toads, and European cultures treated toads with more fear and loathing than frogs. Viewed as poisonous creatures and carriers of disease (and warts), like frogs, they could also act as witches’ familiars, their metamorphosis from aquatic tadpoles to semi-terrestrial adults signifying a supernatural potential for bodily change. But the perceptions weren’t all negative. Alchemical texts incorporate toads as symbols — that metamorphosis trope again — and in his 1608 History of Serpents (frogs and toads being classed within the reptilian family), Edward Topsell referred to the toad as the ‘most noble kind of Frog, most venomous and remarkable for courage and strength’.

I pinched that Topsell quote from Charlotte Sleigh’s book, Frog, a dense and entertaining survey of frogs and toads through natural, scientific, and cultural history. Taking her lead from scientific biology, which recognises no distinction between frogs and toads and treats them as members of an overarching Anuran order, Dr Sleigh uses the terms ‘frog’ and ‘toad’ interchangeably for large parts of her book. This leads to one or two jarring moments, as when she refers to Mr Toad from The Wind in the Willows as a frog. That usage would outrage Toad of Toad Hall. Still, the reader of Dr Sleigh’s book is left wondering why toads have received more hostility than frogs in the past. Even in the fairy tales, princes are turned into frogs, and not toads. I wonder if their means of locomotion could have something to do with it. Frogs hop and leap, and appear livelier than their cousins, who simply walk - and squat. That word ‘squat’ is invariably linked with toads, used by poets as different as John Milton and Philip Larkin. Toads squat and they stare. Frogs are too busy leaping off to catch your eye.

Just as I left this Wey-side toad behind, a cyclist came hurtling along the path. I asked her to watch out, just in case it had wandered back on the path. She smiled and nodded, looking at me as if I might be the self-styled head of the local toad cult, i.e. completely bonkers. And as she rode off, at roughly the same speed at which she’d arrived, I thought that, yes, Anuran-like, my own metamorphosis into eccentric busybody was complete.

Notes on reading

The enchantments of the new Merlin

I always have mixed feelings before re-reading a book that had a profound effect in my youth (and isn’t that really the age when the most profound effects of books occur?) There is the hope that the original, thrilling magic might still be there, waiting to be unleashed once more. And there is the trepidation that the experience will be a disappointment, or a bore, or even an indictment of one’s youthful naiveté. More often than not, the re-read is a let-down. What seemed original now appears hackneyed; what seemed profound now appears pretentious; what chimed with one’s sense of truth now rings hollow.

This is mostly the effect of age and experience. The young mind that devoured books indiscriminately has developed an armour of critical thought. The brutalities and disappointments of life take their toll. But sometimes, still, the old magic is there, as potent and beautiful as before. And sometimes the book works in a different but equally mysterious way, reconnecting the man to the child one was then, to the thought and emotions one had then.

I can’t remember exactly when I first read John Michell’s The View Over Atlantis, but it must have been one of the books I stumbled on in the local library during the voracious reading of my teenage years. Michell’s book, and his outlook, was something new to me and I gobbled it up. There is something very appealing about esoteric thought to the adolescent mind, the secret knowledge that will reveal the underlying patterns beneath the chaos of the experienced world. It would be wrong to say that Michell changed my view of the British landscape; the truth is, he did as much as anyone to form it at that impressionable age.

And so I picked it up again recently. The Thames & Hudson revised edition, titled The New View Over Atlantis and published in 1983, had been sitting on my shelves for quite some time, years in fact. Perhaps that trepidation I mentioned before had been stalling me. The first edition was published in 1969 and quickly became a seminal text for the Age-of-Aquarius counter-culture. In fact, Michell founded a genre, or as he might have preferred to characterise it, a field of studies, which came to be dubbed Earth Mysteries. There were two key researchers whose work Michell combined and elaborated on in the book. One was Alexander Thom, the Scottish engineer who made painstaking measurements of British megalithic sites, including Stonehenge, and had argued that these sites were laid out according to astronomical principles. The other was Alfred Watkins, whose 1925 book The Old Straight Track rediscovered the supposed network of ley lines, straight tracks across the landscape, that linked many prehistoric sites and ancient landmarks in Britain.

Thom and Watkins were both practical, empirically minded men, and neither was given to mysticism. In The View Over Atlantis, Michell used their ideas to build a whole new theory of an ancient Atlantean civilisation, whose philosophy, science, and technology had been handed down to many ancient races, including the Britons. Watkins had thought that ley lines marked trade routes or ritual pathways. Michell proposed instead that they indicated the flows of electro-magnetic energy fields that ancient Britons harnessed for a variety of purposes, including the fertilisation of crops and the transportation of large objects (such as the Welsh bluestones found at the Stonehenge site).

Michell took Thom’s researches, merged them with his own on Glastonbury Abbey and the Great Pyramid, and proposed that all these sites were designed using sacred geometry whose dimensions were proportional to the dimensions of the earth and the heavens. There is more, much more, to Michell’s argument than I can do justice to here and besides, that’s not the point of this post.

‘The fate of our times,’ wrote the sociologist Max Weber, ‘is characterised by rationalisation and intellectualisation and, above all, by the disenchantment of the world’. Weber thought that for pre-modern societies, ‘the world remains a great enchanted garden’. Much of the appeal of The View Over Atlantis lies not in its detailed claims but in how it re-enchants the British landscape. And whether or not you accept Michell’s theories, you have to admire his imagination.

Michell himself was a fascinating character, a unique blend of old Etonian, English eccentric, eighteenth-century antiquarian, and counter-cultural hippy. By giving Glastonbury such a central place in The View Over Atlantis, he, as much as anyone, was responsible for turning the town into the New Age centre it is today. He designed the pyramid stage at the first Glastonbury music festival and married the Archdruidess of Glastonbury later in life. The obituaries of Michell referred to him as a ‘modern Merlin’ or a ‘New Age Merlin’. So far as I know, he never managed to summon the earth energies that he spent so much time studying. The View Over Atlantis is both his grimoire and his monument, a wonderful book, not despite, but because of its peculiar blend of rationality and fancy.

Notes on the here and now

Very white

I was sitting in a pub in Suffolk, chatting to the barmaid. She’d just moved back to England after living in the United States for many years. She was enjoying her new life and extolling the pleasures of the small town she lived in now. ‘But,’ she added at the end of the paean, ‘it’s very white’. She said it almost apologetically, with little conviction. On the surface, it was as phoney and empty a gesture as when an atheist who finds themselves in a church service says ‘Amen’ at the end of the prayers. But it was also a signal, whose meaning was something like, ‘I may live in a town whose population is 95% white but I’m not a racist, honest, I’m a Good Person’.

‘Very white’ and ‘too white’ are phrases you hear a lot these days, often from people who’ve decamped from a big city, usually London, to a small town or village. Unlike the barmaid I met, many of them really mean it. Having fled the metropolis to escape the crime, violence, filth, and general unpleasantness that are integral to the contemporary London experience, they arrive in their little English market towns and find them all a bit, well, dull.

Sure, the people are friendly, the streets are clean, there are no machete gangs, and you can trust the neighbours to take an Amazon delivery for you. But that isn’t enough. One problem is that here, so far from the rumble-tumble of the ‘world city’, you’re confronted with your bland, irredeemable middle-classness. Living in London, for all its downsides, meant that some of that ‘edginess’ and ‘vibrancy’ rubbed off on you and made you, or so you felt, less boring. Now you’ve lost it all.

So you settle in to your new life and your biggest gripe (unless that is, Waitrose doesn’t deliver to your area) is that it’s all too white. Of course, you wouldn’t dream of complaining on one of your holidays that St Lucia, say, is very black, or that Bodrum lacks diversity. That’s different. And whiteness is different — everyone knows that. There’s just too damn much of it. Even the local Indian restaurant isn’t as good as the ones in London, and in any case, you secretly despise the staff for their theatrical deference and inauthentic cuisine.

The only possible excitement that might come along, you think as you sip your Wine Society Malbec, is that these privileged white neighbours of yours might harbour some dark secrets. Might there be a local child abuse ring? Or a swingers’ club? Or a pagan cult that sacrifices animals — or even babies — on special occasions? Yes, a bit of indigenous English folk-horror — that would liven things up all right.

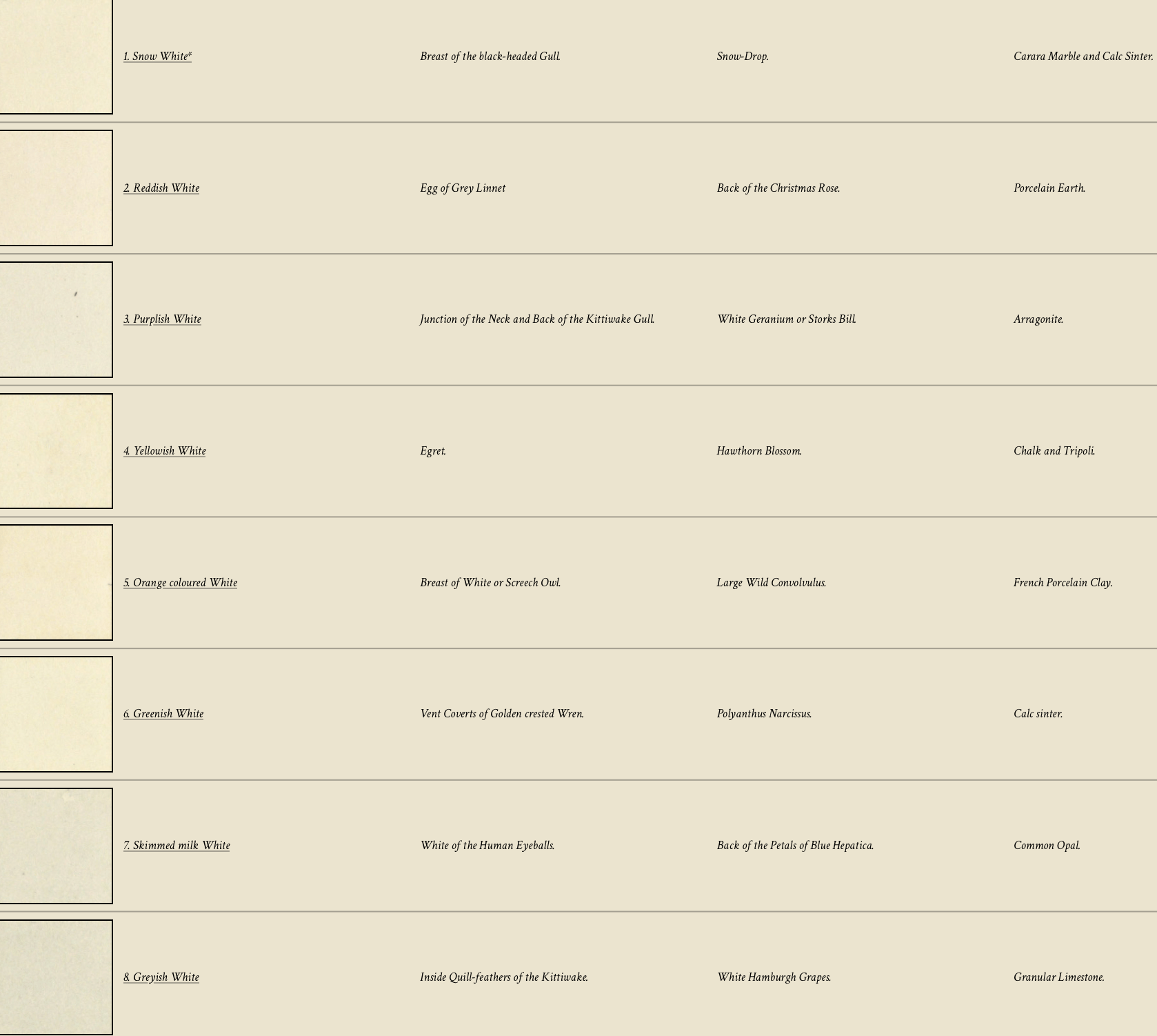

[Image © Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours ]

From the photo album

Penrose Paving, Mathematical Institute, Oxford

‘As you can see, there are just two shapes of tile involved. What makes these tiles special is that the resulting tilings are necessarily non-periodic: it is not possible to create the tiling by taking some (potentially very large) section and repeating it over and over again. A set of tiles with this property is called aperiodic.’