Welcome to the second issue of my relaunched newsletter. If you subscribe I’ll send you a free copy of my Microcosmos Fiction Magazine, containing five original stories. Thanks for reading.

Notes on places

A shopfront in Aldershot

Aldershot, whatever some may say, has its charms. The (former) premises of J. Salter and Sons stand on the High Street, a curio amid the inferno of fast-food joints, pound shops, cash advance merchants and shabby franchises. This business, with its small workshop above the shop, was once the world’s leading manufacturer of polo equipment. Aldershot, the traditional home of the British Army, was also a centre of the sport of polo.

James Salter, from Exminster in Devon, began repairing polo sticks while he was serving with the Royal Artillery in India. Having returned to England and retired from the army, Slater opened his business in 1884. His son Sydney succeeded him and then Raymond Turner, once apprentice to Sydney, took the reins. When Turner retired in the mid-nineties, Sean Arnold, a sporting antiques dealer, bought the premises. With Mr Arnold now retired, the shop is closed. That century of craftsmanship and tradition has ended and will never be revived.

The shop front still carries illustrations of classic British sporting venues: Hurlingham, Windsor, Wembley, St Andrews, Crystal Palace, Ascot, Lords, Wimbledon. This blazonry on the dusty windows of an obscure shuttered shop in Aldershot is a poignant memorial to a more innocent sporting age: before image rights, before doping scandals, before institutionalized corruption.

Notes on reading

Lost movies

In his history of France in the 1930s, The Hollow Years, Eugen Weber notes: ‘Of two thousand French films shot between 1930 and 1950 only a quarter survive, and most of those that we still view are more or less glum.’ Leaving aside the matter of glumness, this is a staggering number of lost movies. How did so many come to be lost?

During this period, movies were printed on nitrate film. This material was not only highly flammable but also deteriorated rapidly if not kept in controlled conditions. In 1937, a fire in the storage vault of the US company Fox Pictures destroyed all the negatives of the company’s pre-1935 films. Cinema in this period was not regarded as an art form worth spending large amounts of money on preserving. It was, from its earliest days, a cold-bloodedly commercial enterprise. Production costs meant it had to be. The twin perils of catastrophic loss, as in a fire, and the simple entropy of physical decay, account for some of the losses.

But in fact, and again this does not just apply to French movies, the bulk of loss was down to deliberate destruction. In his book, The Classic French Cinema, 1930-1960, CG Crisp writes of lost French movies:

Those losses arise from the fact that the films were subject to a purely commercial regime, which saw them thrown out once audiences lost interest, or processed to salvage reusable materials. By about 1920, the earliest films had all begun to seem ‘out-dated’: Pathé had stripped the gelatine off all his early productions to recuperate the base, and Méliès burned all his copies in 1923, giving away the negatives to a salvage merchant. Again, after 1930, silent films came to seem ‘out-dated’ and suffered the same fate. Toward 1950, the switch from nitrate to celluloid caused past production to be abandoned for a third time.

France does seem exceptional in its losses. ‘The situation is much worse in France’, according to Crisp. Other leading cinema nations — Germany, Sweden, the UK, and the UK — established national film archives in the 1930s. France relied on the efforts of individuals such as Henri Langlois, who co-founded the Cinémathèque Française.

You cannot help wondering about the treasures lost in this period. Would Eugen Weber’s impression of the glumness of French films between 1930 and 1950 have held if a more comprehensive archive was available? Impossible to say, and as his book describes in immense detail, the Thirties was not a happy decade for France.

It’s a reminder of the fragility of art and of how contingent its survival can be. Beowulf, the greatest Anglo-Saxon poem, is preserved in a single thousand-year-old manuscript, and that almost perished in a house fire in 1731.

But in the last fifty years, film preservation has come into its own as a scholarly pursuit. Digital storage is the medium, and cloud-based backups are the recovery method. What could possibly go wrong? Digital, short of a civilizational breakdown or an EMP catastrophe, is forever, isn’t it? One problem is that digital formats and standards change, and there is, as far as I know, no internationally agreed standard for film preservation. But as we know, servers crash, backups fail, and archives are hacked.

Samuel Johnson thought public inscriptions should always be written in Latin, a language of guaranteed longevity. He was making a point about the message and not the medium. But consider how much of our knowledge of the ancients is engraved on stone. Perhaps an alternative to digital preservation would be to carve the classic movies, frame by frame, onto stone tablets — with Latin subtitles, of course - thereby ensuring their survival through the future, unpredictable millennia.

(The picture at the top of this item shows Theda Bara in the 1917 film Cleopatra, one of the movies lost forever in the Fox Pictures fire of 1937.)

Notes on writing

The almost incredible

I am very fond of coincidences in plots and situations that are almost but not quite incredible, as in the audacious plan set forth in the first chapter of Strangers on a Train by one man who has known the other passenger only a couple of hours; the chance selection of Tom Ripley, potential murderer, by the father of a young man, as an agent to bring that young man home from Europe; the unlikely and unpromising meeting of Robert and Jennie in The Cry of the Owl, when Robert appears to be a prowler and Jennie ignores this fact and is drawn to him.

Anyone who admires Patricia Highsmith’s fiction will forgive her this fondness for the ‘almost incredible’ and will find these coincidences perfectly believable in the settings and atmospheres she conjures. Coincidences are stitched into the fabric of life and we have all experienced them, though perhaps not as frequently and significantly as the inhabitants of fictional worlds. But there is a considerable art in using them without making the story seem ridiculous. Highsmith’s point here is signalled by the world ‘almost’: in their use of coincidence as a plot device, the writer may stretch the reader’s belief, but they must never snap it.

Victorian writers were especially fond of coincidences, as anyone who’s read Oliver Twist or Jane Eyre will know. Oliver, out on an expedition with the Artful Dodger, just happens to pick the pocket of one of his father’s old friends. Jane, wandering the moors, just happens to be taken in people who turn out to be her cousins. These are almost incredible coincidences, and yet we accept them and keep reading. I’m not sure that would be the case if a living writer tried to pull such a trick.

In the last book I published, there are several chance meetings that help drive the plot. As I worked on the book, I told myself that these were believable and on the ‘almost’ side of incredible. There is the setting, 1930s Nice, a city not so big that characters mightn’t come across one another in its central district, and there are the characters themselves, each with their own reasons to be in a particular place at a particular time. In other words, the characters come together not wholly at random but because they have cause to be where they are at that time. I think it works with it, though that will be for the reader to judge.

In the passage quoted above, Highsmith seems to view the almost incredible as being to do just with coincidence. But in one of examples she mentions, there is more to it than that. It is not merely that Guy Haines meets Charles Bruno on a train, and it is not merely Haines has a wife and Bruno has a father each wishes to be rid of. It is also that Bruno proposes that they swap murders, so that each disposes of the other's problem. Almost incredible? Yes. But ingenious writing nonetheless? Completely.

There are, of course, striking coincidences that involve inanimate objects as well as people. Arthur Koestler, one of the twentieth-century’s most interesting and wide-ranging writers, was preparing a newspaper article on the 1972 World Chess Championship match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky, which was to take place in Iceland. Koestler visited the London Library to do some research. He recalled the visit in an article on coincidences for the Sunday Times:

I hesitated for a moment, whether to go to the ‘C’ for chess section first, or to the ‘I’ for Iceland section, but chose the former, because it was nearer. There were about 20-30 books on chess on the shelves, and the first that caught my eye was a bulky volume with the title Chess in Iceland…. This type of coincidence, involving libraries, books, quotations, references or single words in special contexts, is so frequent that one almost regards them as one’s due.

Koestler was so intrigued by the operations of coincidence that he devoted a large part of his book on ESP, The Roots of Coincidence, to the subject. The book cited the theories of Paul Kammerer, Carl Jung, and Wolfgang Pauli — respectively a biologist, a psychologist, and a physicist — each of whom believed that what is commonly called coincidence is in fact an indicator of some underlying principle or law of reality. On this view, the Universe operates in two modes, the familiar one of cause and effect and the less familiar but equally real one of acasual connection. It is the latter that is observed in meaningful coincidences. Kammerer called it the Law of Seriality, while Jung used the term Synchronicity.

One of my favourite examples happened to the writer Anne Parrish, and was recounted in the New Yorker in 1932:

True story about an adventure that befell Anne Parrish one June day in Paris. She was wandering through the old book stalls along the Seine with her husband who had been there before. He sat down at a table on the quai and let her go rummaging. She came over with an old English book for children, called ‘Jack Frost and Other Stories’. Only paid a franc for it. Hadn't seen anything like it in twenty years. Not since she was a child. It contained her favourite nursery stories. Even remembered one of them. Her husband looked at it. He admitted she must have know it in her younger days. On the flyleaf was her name and New York address.

You couldn’t make it up — or rather you could, but no reader would accept it. To return, finally, to Patricia Highsmith, I think the fiction writer must stick to the almost incredible, and leave the crazier stuff to reality.

(The picture at the top of this section shows Robert Walker and Farley Granger in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1951 movie version of Strangers on a Train.)

From the photo album

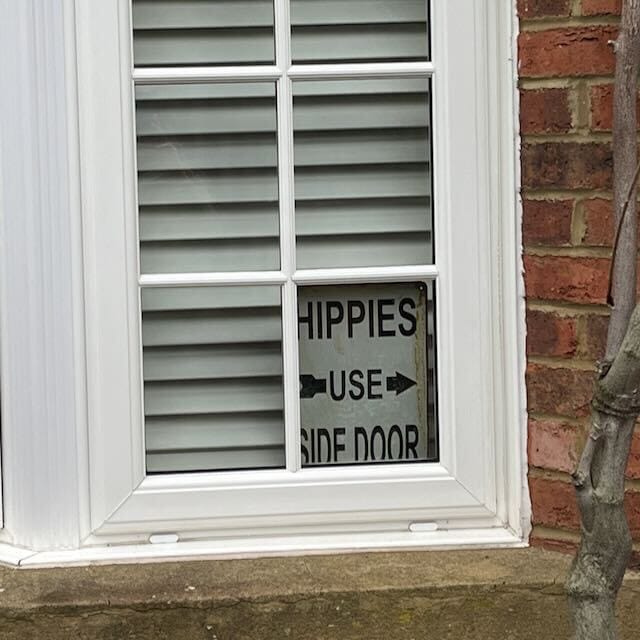

Hippiephobia, Aylesbury